ELIZA Bonini and the AI Turtles

Published:

TL;DR: ML reasoning systems are going through an exciting phase transition that escapes our understanding; we neither can nor want to stop it, but this requires an AI Safety approach similar to autonomous driving (engineering + human accountability) to avoid the pitfalls of AI anthropomorphization.

The amazing results of OpenAI’s o3 system got everybody to reassess their predictions about the future, again. Brad Porter (CEO of CoBot, one of our portfolio companies at Calibrate Ventures) reposted his excellent essay “Approaching the AGI Asymptote” and re-analyzed his conclusions in this linkedin post.

The main points Brad made at the time were about:

1) how do we know we are approaching AGI (“the more convoluted the arguments distinguishing machine from human intelligence become, the closer we actually are to artificial general intelligence”),

2) who gets to say if we need to worry or not (more than just AI luminaries, which was echoed recently as “let’s stop deferring to insiders” in this excellent “AI snake oil” blog by Arvind Narayanan),

3) an AI Safety framework based on ethical considerations of ever more capable AIs.

Brad re-analyzed his thinking and largely stood by it, with some caveats and questions that got me to write some of my updated thoughts on AI safety.

In a nutshell:

1) progress cannot and should not be stopped, but we need to be extra careful,

2) to do so, and based on my personal experience in autonomous driving and robotics, we should be wary of anthropomorphism (the ELIZA effect) to focus more on an engineering approach to AI safety while emphasizing human responsibility, especially as AI systems escape our understanding (Bonini’s paradox).

So who is ELIZA Bonini and what does it have to do with turtles?

Bonini’s Paradox and the Inscrutability of Modern ML Reasoning Systems

First of all, ELIZA Bonini is not a real person (or maybe it is, but that would be unintentional). It is the conjunction of two ideas latent in Brad’s essay and present independently in much of the commentary on AI throughout history: Bonini’s paradox and the ELIZA effect. They are rarely presented together, but I think their intersection is instrumental to make the case for AI safety as an engineering discipline (vs focusing mainly on ethics). So let’s start with Bonini.

Brad’s aforementioned definition of the AGI asymptote is what reminded me of Bonini’s paradox and, pardon my French, Paul Valéry’s elegant quote: “Ce qui est simple est toujours faux. Ce qui ne l’est pas est inutilisable”. (“What is simple is always false. What is not is unusable.”) As stated in the article above, Bonini’s paradox is: “As a model of a complex system becomes more complete, it becomes less understandable.”

This paradox, grounded in the famous “no free lunch” theorems, is often discussed across sci-fi literature (e.g., in Asimov’s Foundation series), developers of simulation tools (e.g., the resources needed to build and run “world models”, a very hot topic in AI startups like Runway, World Labs, Odyssey, or Wayve), as well as neural scaling laws and the galloping capital and energy needs of AI datacenters (e.g., Meta’s 2GW Louisiana one).

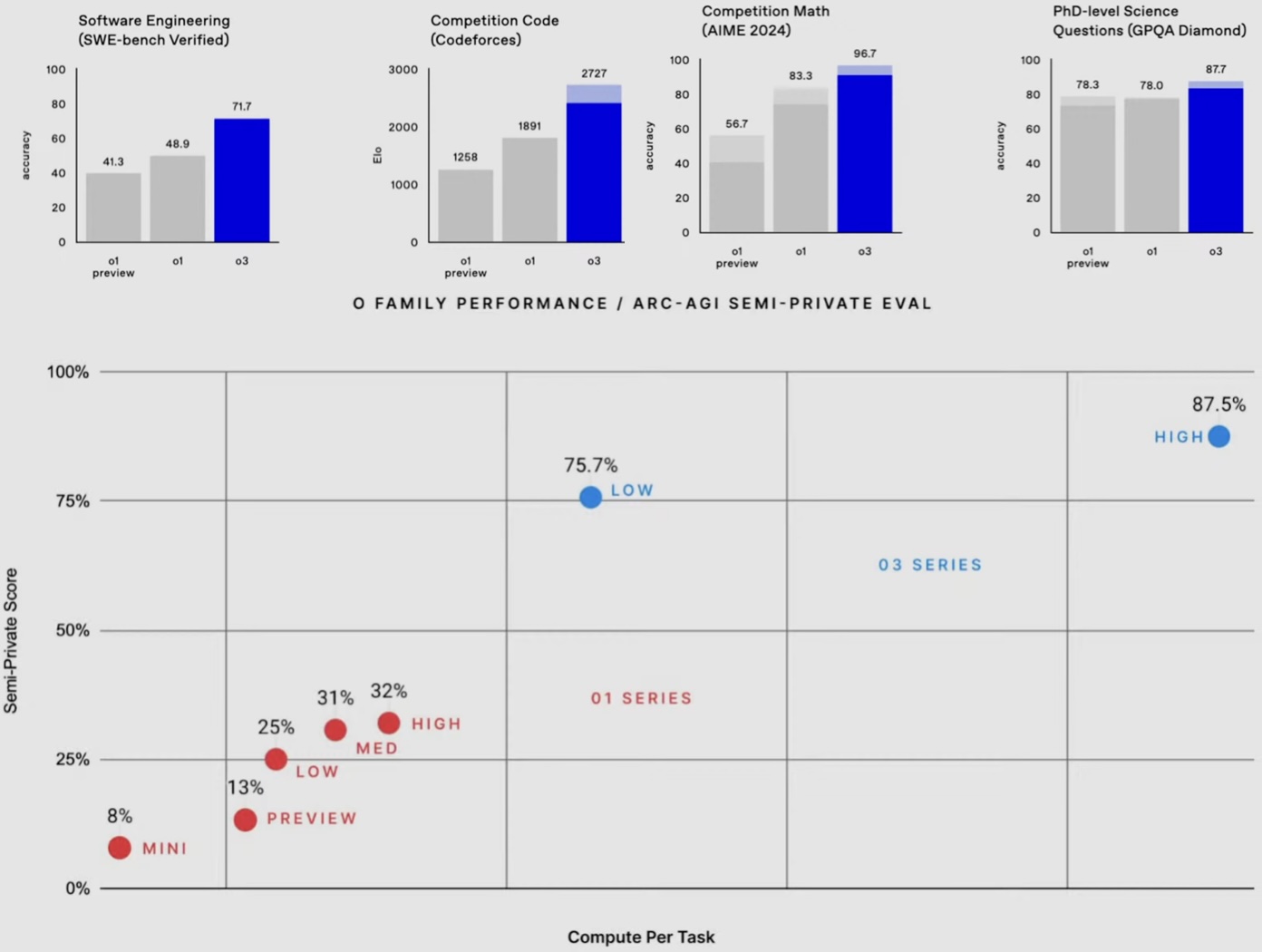

At a technical level, Bonini’s paradox is becoming a central concept in LLMs now that there is a scalable path towards “reasoning” (the inference-time scaling techniques used in o3 for instance). Normally, it is much easier to verify a solution than to find it (in an echo of the good old P vs NP problem), but evaluation of sophisticated AI models like o3 is becoming extremely challenging as we scale to harder tasks. We are rapidly saturating standard benchmarks, even the ones like ARC-AGI that stand in the twilight of Moravec’s paradox (easy for humans, hard for AI), cf. o3’s results below taken from the o3 announcement and this nice summary by Nathan Lambert.

Hence, we are increasingly leveraging AI to evaluate itself (cf. LLMs as judge and other techniques mentioned in the aforementioned o3 announcement video). Note that such a recursive use of AI is common for training (that was actually one of my first papers, a common autonomous driving industry practice in uncertainty-based active learning, and a big part of modern pseudo-labeling techniques as scaled up in Meta’s SAM-2 approach), but it is a recent focus for testing, out of necessity.

In the words of Ilya “Bonini” Sutskever himself: “The more it reasons, the more unpredictable it becomes.” To me, “it” refers to both parts of the system (models, training, and now testing) and the system as a whole. Thus, AI is rapidly escaping our understanding. That’s just a fact, and the cat is out of the bag. I don’t think we can put it back, nor do I personally want to (yes, I’m a cat person). It’s just too useful and exciting!

So how are we going to mitigate the risks of ever-more capable, and hence inscrutable, AI? What are even the risks?

The ELIZA Effect is a Distraction for AI safety

To tackle this question, I would normally need to start by rigorously defining foggy concepts like “AGI”, but, thankfully, this is beyond the scope of this blog. Instead, I will focus on Brad’s definition of the aforementioned “AGI asymptote” in terms of the distance w.r.t. human explanations. This definition seems to elegantly address Bonini’s paradox by mapping to human behavior (e.g., a tendency towards mysticism in our explanations of phenomena that transcend our understanding), something we can observe and measure and test, thus scientific!

However, in my humble opinion, the ensuing AI safety framework sometimes teeters on the edge of the anthropomorphization trap. This is where ELIZA finally comes into the picture as a distraction for AI Safety.

The ELIZA effect is a tendency to project human traits onto interactive computer programs. The effect is named for ELIZA, the 1966 chatbot developed by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum (and something I personally learned from Gill Pratt).

We are lightyears ahead of ELIZA (the chatbot) now with incredible technology like GPT-4 and o3, so the ELIZA effect is more prevalent than ever. However, the illusion it creates is much more impactful now, especially when it comes to safety. The ELIZA effect indeed tends to overemphasize anthropomorphic safety concepts vs functional ones. Morals, intentions, fear, etc are all human concepts. They relate to organizational or regulatory constraints on people, developers and users, more than implementation details (cf. the vetoed SB1047 California bill). We regulate moral entities, people, not AIs. An AI (or a self-driving car for that matter) cannot kill someone and go to jail. The users or developers of these tools can.

At a technical level, the ELIZA effect is even more potent now, as the progress in AI is largely rooted in imitation learning. Anthropomorphization is an effective technique for users to squeeze the most juice out of LLMs (including jailbreaking!), because it projects inputs closer to the training data (all of them: pretraining, SFT, RLHF). Same for developers, for instance with the latest progress in inference-time scaling and chain-of-thought, where developers and users assess safety by attributing meaning and intent to computationally derived CoTs (textbook ELIZA), whereas this is mathematically just statistical alignment to avoid out-of-domain generalization issues (essentially what prompt engineering does, cf. Subbarao Kambhampati for interesting posts on these topics).

The heart of ML remains unchanged in my mind: it is the i.i.d. assumption (data are independent and identically distributed). The fact that it works so well is what’s amazing and does not warrant anthropomorphization to be amazed!

Safety is an Engineering Problem

So what if we anthropomorphize AI too much? From my perspective building ML-heavy autonomous driving and robotic systems, the ELIZA effect hurts on both ends: it slows down adoption by skeptics and creates real engineering pitfalls for trailblazers by creating philosophical distractions. Those are the real harms of ELIZA Bonini, the tendency to anthropomorphize AI compounded by Bonini’s inevitable paradox creating the desire for transcendental (or at least philosophical) explanations. If I learned one thing from Autonomous Driving, it is that safety is about engineering, not philosophy.

(As a side note, what’s funny to me is my own reversal of attitude over the years as I deployed more and more of my initially crazy research ideas (e.g., around sim-to-real transfer, end-to-end learning, and self-supervised learning). I went into AI almost 20 years ago for philosophical reasons, but stayed because of the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics and engineering 😉)

AI safety should be closer to Functional Safety to minimize the risks of catastrophic failures in complex safety-critical systems (LLMs have gotten good enough to fit that category). Functional Safety experts are key to making extremely capable AI systems safely deployable by reasoning about the safety of the intended functionality (SOTIF) instead of the internals of the system, which can be a black box (that’s the key!). I personally learned a lot from folks like Sagar Behere and his team in the early days of TRI (although any misunderstanding is my own!). Brad’s article discusses related ideas (e.g., around access controls, which in AVs relate to Operational Design Domain, ODD), but sometimes with terms that ring a bit too anthropomorphic or philosophical to my ears (e.g., around ethics and intent).

From the Age of Training to the Age of Testing

Of course, AI practitioners like Brad and many others have incredibly complex and thorough testing, verification, validation, and CI/CD systems. However, the ELIZA effect is so strong now that many non-practitioners (e.g., non-technical CEOs) might think that AI Safety is primarily a philosophical issue, and thus might dangerously underinvest in safety engineering. As the productivity of the builders keeps skyrocketing by recursively leveraging the tools they build, so must the productivity of safety engineers.

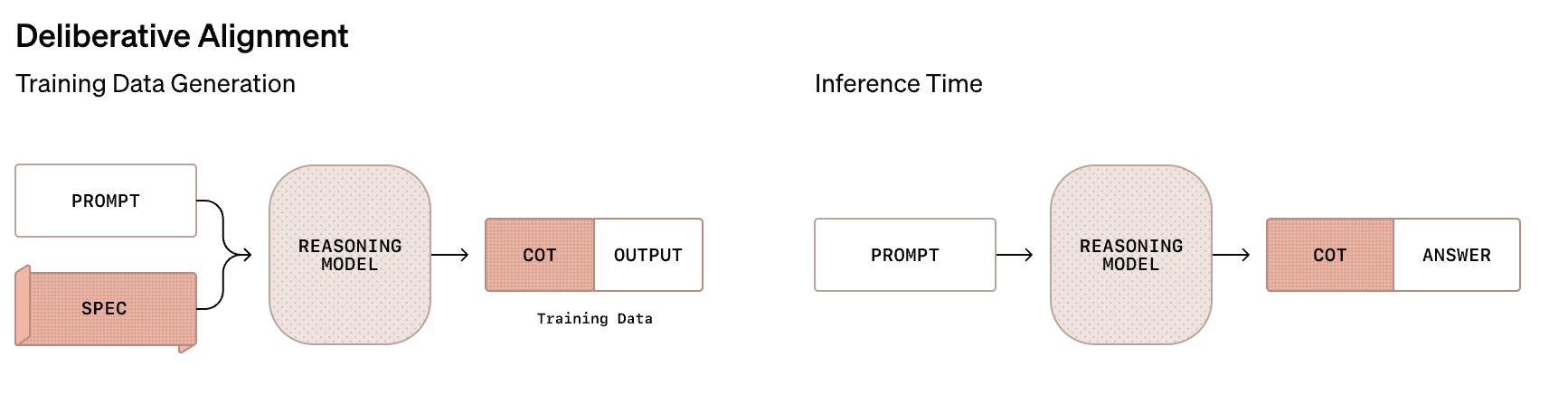

What makes safety engineering extra hard is that using the same tools as the builders is not enough for the testers. As an example, OpenAI’s latest deliberative alignment technique seems very effective for alignment, but it still relies on the interpretation of computational CoTs (chain-of-thoughts) to evaluate safety (cf. the detailed explanation and visuals to explain the ROT-13 example).

What happens if the CoTs correspond to abstract and complex reasoning that is effective but hard for us to understand (Bonini’s paradox)? What if o3 (or o4, o5…) finds a new way to build nuclear fusion reactors with CoTs beyond our current understanding of physics? We can’t just rely on ELIZA Bonini’s vibes and high-level explanations to dumb things down to our level. We can’t also “just build it and see” (that approach does not scale well with risk, cf. the previous industrial revolution and climate change).

This shows the core of the issue: the ratio of tester-to-trainer abilities must grow superlinearly due to the current “Field of Dreams” approach to testing (“just build it, testers will come”) and the fundamental asymmetry of the costs: failing to build a better system is ok, failing to gate a catastrophically bad release is not. Testers must anticipate and move to where the puck is going, not where it stands.

This is why we need to move from the age of training to the age of testing. In data-centric ML terms, the test sets need to eventually dwarf the training sets. We are very far from that today. We are talking tens of trillions of tokens on the training side vs mere millions on the test side: that is a 7 orders of magnitude difference between training and test data! Testing in public obviously has limits as the capabilities of the systems continue to scale. That’s why simulation is so important in driving and robotics (or Embodied AI in general). We need more safety engineering solutions like that for “AGI” or face the consequences of the ELIZA effect: attempts to stop progress out of fear or failure to constrain naively optimistic deployments with potentially catastrophic consequences. This is the grand challenge of the scientific and engineering discipline behind AI Safety.

Humans at the wheel: it is not AI all the way down!

I don’t want to completely disregard philosophical and ethical considerations of course. Maths and engineering are great, and everyone should invest way more into testing as outlined above. But that is not enough. AIs can’t do all the jobs – judge, jury, and executioner. It is not turtles, huh sorry AIs, all the way down. Ultimately, there are people at the bottom.

No matter the ideas, it’s always about people in the end. This is easy to forget in a period of rapid technological progress. I personally remind myself of that periodically thanks to a quote from one of my favorite books of all time, “Creativity Inc.” by Pixar founder Ed Catmull (one of the few management books applicable to research teams): “Ideas come from people. Therefore, people are more important than ideas.”

Humans are responsible and should be held accountable. In AI we talk a lot about “human in the loop” systems, scalable oversight, etc. But with the loops themselves becoming increasingly faster and more complex (and thus inscrutable per Bonini), the only scalable concepts are responsibility and accountability of humans (precision warranted to not fall for ELIZA again). Even if we use AI to help ourselves govern ever more powerful AI and it feels like turtles all the way down (e.g., with inscrutable chain of thoughts and scary hints of recursive self-improvement loops), in the end, our human hands are on the wheel, no matter how much horsepower there is under the hood. In practice, someone has to actually ask (i.e. program) the AI to improve itself. That person is responsible and accountable. There is power in the “maybe not” (for recursive self-improvement) remark by Sam Altman at the end of the o3 video. That would make for a great climbing t-shirt by the way.

Furthermore, we can expect, and in fact demand, this level of accountability, because no matter what happens at the model level, the model itself is just a small part of a complex system (as I discussed in my recent comment to the aforementioned “AI snake oil” blog of Arvind Narayanan et al). That ML system is itself part of a product with a specific purpose, set itself by a company, which is composed of accountable people, from developers to leaders. It’s people all the way down.

Conclusion

As the unrelenting wave of amazing results and the prevalence of the ELIZA effect shows, we are undergoing a phase transition in the capability of AI systems and must contend with the consequences of Bonini’s paradox. Relying on human understanding for safety does not scale. The attraction for ELIZA Bonini, the tendency to anthropomorphize inscrutably complex AI to reassure ourselves, should not distract us from our work in safety engineering and moving from the age of training to testing while emphasizing human accountability, even if only at the bottom of a long CoT (chain-of-turtles).

What about the argument that this might stifle progress? Not slowing down progress was important while we didn’t know if it was possible to get this far, but now… things might be different. You don’t need a speed limit when all cars can only go at 20km/h, but you do when they can go at more than 100km/h. Note that you can still go as fast as you want on a race track or a crazy German Autobahn, but you can’t in a school zone. What is the equivalent for AI? Good question 😉

Finally, more rigorous safety engineering and accountability might actually be important not just to survive but to win in the long term, as evidenced by the state of the autonomous vehicle industry. The best AV companies are indeed the ones that hired and empowered Functional Safety experts and publicly and transparently committed to safety engineering with a high degree of accountability. Considering the success of this approach in AVs, especially Waymo’s, the industry leader in both commercial deployment and safety (cf. Waymo’s thorough approach to safety), I hope to see more of that in AI broadly, both in terms of implementation, public discourse, and accountability.

What do you think? Please let me know on twitter or linkedin. And remember, it’s not turtles (or AIs) all the way down: ultimately, there is always a human at the wheel.