LLM and reasoning games: Is DeepSeek-R1 Good at Mastermind?

Published:

Some simple logic games are surprisingly hard for current “Large Reasoning Models”, making this a promising research direction, as recently noted by Andrej Karpathy in response to the TextArena release.

A good example found by Brad Porter is the classic game Mastermind, which o1 and o3-mini struggle with. I mostly reproduced Brad’s results, but I haven’t seen people try it with DeepSeek-R1 yet.

I was curious about R1’s chain-of-thought (CoT), which it exposes (unlike other models—at least, not yet). So I ran a few experiments on this rainy Sunday morning.

TL;DR: like o1 & o3, R1 is way worse than my 10 year-old daughter at Mastermind, but its chain-of-thoughts are fascinating and show interesting patterns that will get better with data!

Mastermind Experimental Setup

- I used DeepSeek-R1-32b (the Qwen2-32B distilled variant of R1) using ollama on my MBP (

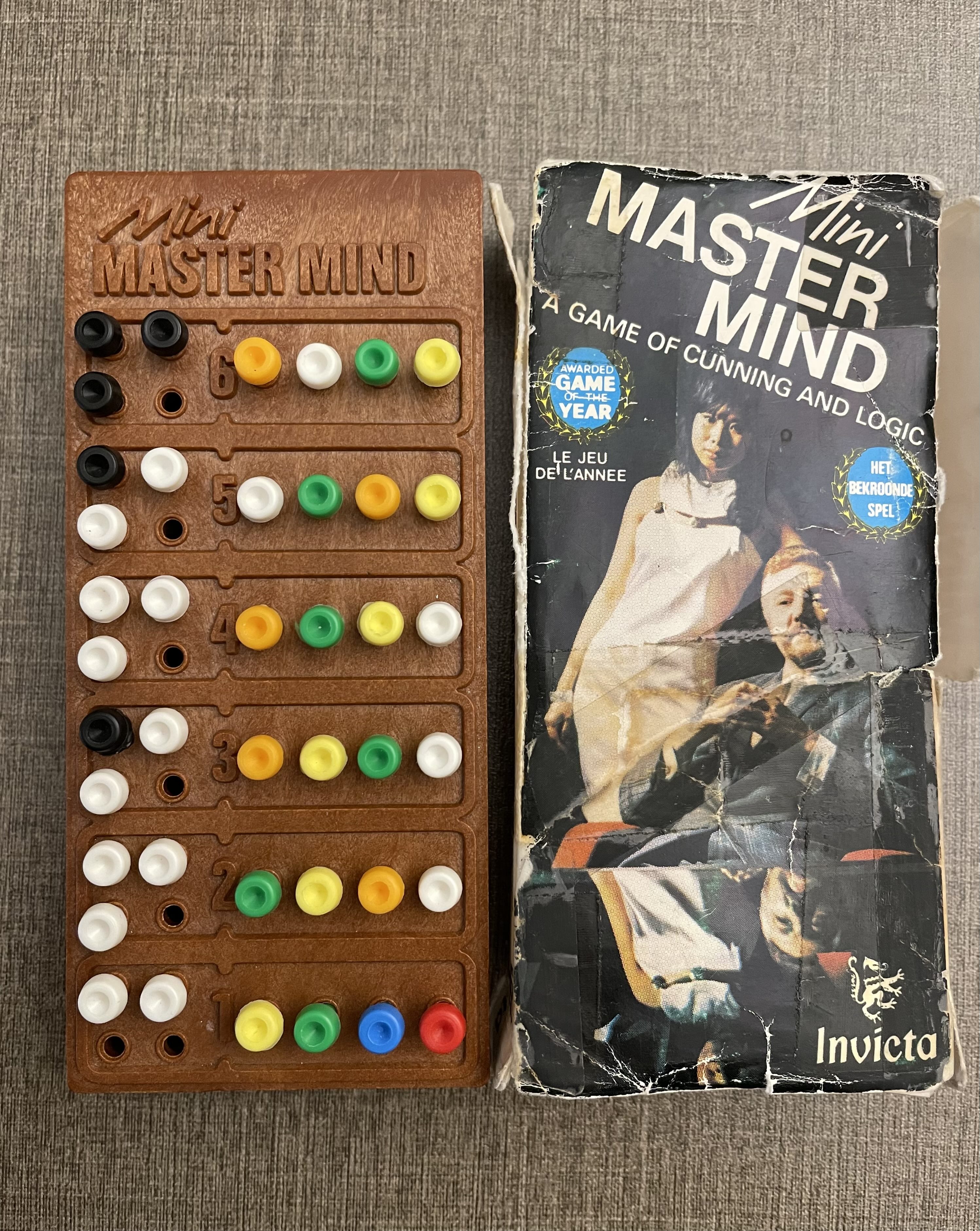

ollama run deepseek-r1:32b). - I have an ancient Mastermind mini game, so I followed the rules of this version, which I explicitly described in the prompt (there are different variants of the game, so I described my version precisely).

- I use the popular PPFO prompting template for R1; my prompt is here:

<purpose>

Mastermind is a code-breaking game where I generate a secret sequence of colors, and you (the AI) attempt to guess it.

The objective for you is to deduce the correct sequence in as few guesses as possible by receiving feedback after each guess.

Feedback indicates the total number of colors that are exactly correct (right color, right position) and the total number of colors that are correct in color but in the wrong position.

The game is won when you correctly guess the entire sequence.

</purpose>

<planning_rules>

- The secret sequence consists of 4 pegs chosen from a set of 8 colors.

- The total set of available colors is: yellow, green, blue, red, orange, brown, black, white.

- Duplicate colors are allowed.

- You make sequential guesses attempting to match the secret sequence.

- After each guess, I will provide feedback using symbols for exact matches and color-only matches.

- You only have 6 guesses allowed before the game ends.

- You should use logic and the feedback from previous guesses to refine subsequent guesses.

- The secret sequence remains fixed until you correctly guess it or the guess limit is reached.

</planning_rules>

<format_rules>

- Color Code: Use single-letter abbreviations for each of the 8 colors as follows:

- Yellow = Y, Green = G, Blue = B, R = Red, Orange = O, Brown = N, Black = K, White = W.

- Sequence Format: Represent the 4-peg sequence as a string of four letters (e.g., YGBR).

- Scoring Feedback is provided as an unordered sequence of 4 symbols:

- "M" indicates an exact match (correct color in the correct position).

- "C" indicates a color-only match (correct color but in the wrong position).

- "X" indicates a peg of the wrong color (not in the secret sequence)

- The feedback symbols are provided in no particular order and do not correspond positionally to the guess.

- Example Feedback: For a guess that yields 2 exact matches and 1 color-only match, the feedback might be displayed as "MMCX" or "XMMC" (the order of symbols is arbitrary).

</format_rules>

<output>

- You will output your guess as a 4-letter string based on the color abbreviations (e.g., RBGY).

- After each guess, I will provide feedback in the form of symbols (e.g., "MCXX") indicating the match results.

- The interaction will continue until you either correctly guess the secret sequence (winning the game) or exhaust the maximum allowed guesses (6).

- You will incorporate the feedback from previous guesses to inform your future attempts.

- I have a secret sequence of 4 colored pegs. Let's play! What is your first guess?

</output>

Caveats

- This is a “vibes” eval (reproducible anecdote), as I only played a few games (N=ridiculously low), because I was reading the entirety of the (very long) thinking traces, assessing the logic of every step, which is obviously not scalable.

- Beyond the scoring of each guess, I infrequently gave some natural language feedback when the model had obviously misunderstood a rule or missed a subtlety (e.g., that scoring is position-independent), as I did with my daughter the first few times we played together.

- Having many precise rules and the use of symbolic notation is not the best fit for an LLM. Playing the game entirely in natural language (i.e. “talking” to the model to give it the score) might work better?

Results

The bad

R1 is not a good Mastermind player.

R1 failed to win at the games we played, even rarely showcasing monotonic progress in the quality of its guesses. If I looked only at the guesses and not the reasoning traces, they would seem pretty incoherent. Performance numbers would be bad in a serious large scale eval.

I doubt that it would change much even with much better prompt engineering, as it is clear from the reasoning traces that R1 understood the game and rules pretty well with my (relatively careful) prompt.

It is possible (likely IMHO) that 32B is not enough for such a game, but I did not have time to try bigger models with some extra compute / time. I’d be curious to hear from people that try though!

The appearance of reasoning or just occasional brain farts?

Overall, R1 clearly lacks a consistent process / method / strategy, as it seems more like fumbling through guesses than following a consistent algorithm. It is definitely not doing MCTS or symbol manipulation. The reasoning / CoT often looks legit on the surface, but this lack of methodological consistency makes the thinking trace feel more like only the appearance of reasoning.

This impression is reinforced by what I can best describe as brain farts, i.e. obvious logical errors out of nowhere. For instance, R1 often jumped the gun and concluded a peg is for sure at a position while the evidence it was enumerating just before was clearly not enough to say that.

A puzzling example, towards the end of a long game:

But honestly, without more information on previous guesses and their feedbacks, it's impossible to

accurately determine. Therefore, based on Guess 5 feedback, the code likely starts with G W O and has a

fourth letter that isn't Y.

So I'll go with **GWOA** as a guess, assuming A is a common letter.

It starts so well, and then decides to go with A (not a color), “assuming A is a common letter”!?

The lack of consistent higher level reasoning patterns combined with these brain farts make it hard to pin down exactly what type of “reasoning” (or the absence thereof) is learned by this statistical language model.

R1 exhibits the classic failure modes of LLMs.

Because, yes, it is just an LLM, albeit a very good one! Prime examples of classic mistakes are partial memory lapses (e.g., forgetting a turn, needle-in-haystack issue) or hallucinations (e.g., imaginary feedback).

However, these mistakes are surprisingly infrequent considering the length of the episode (why it’s a great model!). The low frequency of these known issues is impressive, but often catastrophic nonetheless, as it is used in a reasoning loop. For instance, once it erroneously convinced itself the first peg was orange after guess 3 in a game, then it never questioned it and thus only made faulty reasoning thereon.

This illustrates exactly why autonomy is harder than intelligence: actions have sometimes irreversible consequences. And this is not just in the physical world, but also in this context under a limited set of guesses and compute budget. Decision is fundamentally different than prediction: this is the big hurdle AI Agents have to overcome (with lots of lessons transferable from self-driving cars and robotics!).

But this is also why I like the approach of “reasoning” via CoT in token output space (vs latent space a la Yann LeCun, which I subscribe to for vision/robotics, but less for language). The necessary sampling / discrete choices should force the development of robust closed-loop interpretable reasoning patterns (e.g., assessing decisions that are one-way vs two-way doors, backtracking, taking calculated risks, error correction), as evidenced in some of R1’s thinking traces.

Which brings me to the good parts, and why this experiment is another useful data point in my own model of the realizable commercial opportunity of large reasoning models and agentic AI.

The good

The emergence of reasoning skills is real.

As many reported, R1 can indeed catch some logical errors via self-reflection (“but wait” as a backtracking trigger) and consistency / coherence of its own thought process.

A cool example:

But wait, from GYOW having three correct but misplaced, W might not be part of the code. Maybe I should

exclude W.

Alternatively, if W is incorrect, then from GYOW, maybe G, Y, and O are correct but misplaced.

So perhaps try arranging them differently:

Guess 4: WGOY

But that feels random. Maybe I need to keep some colors fixed based on previous feedback.

This is really challenging without knowing which position is correct. I think I need a more systematic way

to approach this.

Maybe list out all possible positions for each color based on feedback and see where they can fit.

Together with the (oft misinterpreted) training costs, these skills are the source of the hype around DeepSeek-R1 and discussed at length in the thorough (and rare) DeepSeek-R1 research report from the DeepSeek team, so go read that if you haven’t already.

As mentioned in the previous section, it’s far from perfect, but it’s undeniably there and compelling.

The vibes / how R1 feels: a productivity hack?

Surprisingly, the reasoning is often relatable and cute:

But I'm not sure how to interpret this since the feedback is unordered. It's confusing because an "M"

doesn't tell me which position is correct, just that there's at least one exact match somewhere.

Wait, I'm getting confused. Maybe I should try another combination.

This was a surprise to me. Not just how I felt reading the long CoTs, but more the fact that it actually helped with debugging / cooperating. Anthropomorphization continues to be a powerful technique for AI Engineering.

This is obvious for models that are learned by imitation (tons of SFT / RLHF), but it was a surprise for an RL-trained model like R1. I guess the DeepSeek-v3 base model was so strong (the leading hypothesis for why RL worked this time) that the multi-stage training of R1 made it stay close to its human-like training data while learning better reasoning skills.

The accurate multi-step reasoning parts of R1’s output is when the Eliza effect was the strongest for me, and I caught myself feeling impressed or cheering it on (I could read the generation in realtime due to the inference speed on my mac). It is great for “pair programming” with these models, but it creates a strong bias for eval (opposite to the actual performance).

This anthropomorphic bias is why vibes are a double-edged sword, as I wrote about recently when talking about Eliza Bonini and the AI turtles.

Semantic Representation of Uncertainty.

Beyond self-reflection and consistency, another encouraging pattern in the CoT is its semantic representation of uncertainty (“I’m not sure”, “maybe”). It clearly saved R1 a bunch of times when it was going in a wrong direction.

This seems plausible, but I'm not sure. Maybe I should try OWGY as my next guess to see if it works.

It is interesting to think about this in the context of calibration of probabilities, sampling, and other important technical aspects of robust probabilistic modeling. As all roboticists know, uncertainty modeling is key for robust control in closed-loop systems.

Having the thinking trace is a huge advantage.

It is clear conceptually that transparency is better, but in this case I was surprised at how useful it actually is in practice, especially with a human in the loop. In particular, the visible CoT greatly accelerates prompt debugging.

As an example, I had missed a color in the list of possible pegs in one part of the initial prompt, but not in another, which made it inconsistent. I found out only from reading the thinking trace of R1 (“this is confusing”) and thinking it had made another reasoning failure but it was actually my fault… oops.

This is important, as prompts get more complex (agents anyone?) and why I like the idea of putting more structure in AI engineering with tools like Stanford’s DSPy, Letta’s ADE, and W&B’s Weave.

Beyond good systems engineering (separation of concerns, specification, verification, and validation of pre-/post-conditions, etc), process rewards could also be a powerful set of guardrails at inference time, enabling the automated detection of this type of prompt bugs, maybe even adversarial ones that try to do prompt injection to induce faulty reasoning like logical fallacies?

The best kept secret of autonomy: the human in the loop.

Another benefit of reasoning traces is that it enables the end user to give high-level corrective feedback when the answer is wrong based on a misunderstanding due to ambiguity (e.g., a loose application of the rules). That type of “lightweight cheating” drastically improves R1’s performance.

Alright, so I just received some feedback on my latest guess in Mastermind, and apparently, there are two

big issues with how I've been approaching this. First off, someone mentioned that "M" isn't a color, which

confused me because I was treating it as part of my guess. Second, they pointed out that the feedback is

unordered, meaning that an "M" in the first position doesn't necessarily mean the first peg I guessed is

exactly correct—it could be any of the pegs.

Okay, let's start by understanding what "M," "C," and "X" really mean in the context of Mastermind

feedback. From what I recall, "M" stands for "correct color in the correct position," "C" means "correct

color but wrong position," and "X" indicates a color that isn't in the secret code at all or is duplicated

incorrectly.

But wait, if "M" isn't a color itself, how does it factor into my guessing strategy? Oh, I see now—using

"M" was a mistake because it's part of the feedback system, not an actual color. That means I need to

avoid using "M" in my guesses and focus solely on the colors available.

Also, the feedback being unordered is a game-changer. Previously, I assumed that the first "M"

corresponded to the first peg I guessed being correct. But if the feedback isn't ordered, then an "M"

could apply to any of the positions in my guess. That means I need to reinterpret how I use feedback to

adjust my guesses.

This illustrates the final and possibly most important point: Large Reasoning Models are great with a human in the loop, but not ready for full autonomy. The current models are might be good enough to amplify us (humans) or for us to (scalably) manage them in a semi-autonomous system (e.g., OpenAI’s Operator) for certain tasks and certain contexts (the hunt for those killer apps is on!), but we are not yet at “push a button and take a nap while my LLM is doing my job”.

Designing agentic systems to make human-LLM interactions delightful, frictionless, predictable, and infrequent (thus scalable) is key to any product that wants to build on this technology today.

But wait, doesn’t that strongly smell like the lessons from autonomous driving and robotics (the need for supervision at training and inference time)? Huh. (See, I’m good at impersonating R1 now that I read thousands of CoT tokens ^^).

Conclusion

Overall, despite its lackluster Mastermind performance, DeepSeek-R1’s chain-of-thoughts confirmed that this approach is pushing the boundaries of more grounded, coherent, thoughtful, and capable large reasoning models.

It also highlighted the gap between intelligence and autonomy and the need for a human in the loop, even with a clear operational domain like Mastermind. That’s why there is still a lot of work to do to get to the grand vision of AI Agents, to get data from prediction to action, but we are making visible and fast progress!

If you are a founder building a product that can overcome or cleverly hack these reasoning and agentic challenges with a clear path to market, or if you can disprove my very subjective conclusions with concrete evidence, then please reach out!